Only The Strong Survive

Joan Wypijewski

The Nation

August 26, 1996 issue

Growing up, I’m not sure I knew girls like Jill Ciment, but I knew their look–precociously tough, with stuffed bras and bare midriffs, frosted pearl lipstick, raccoon eyes and rat-tail combs–and I knew their anger. Its signature was in the smashed glass around the park near where I lived, in spray-painted obscenities that appeared on the public poorhouse in the morning after their outings, in the broken saplings, torn tulips and hastily abandoned underwear that we children would discover with a mixture of awe and fear. I didn’t know their pain though. When, inexplicably, two such girls once pushed me off my roller skates onto the street with some mean taunt, it never occurred to me that the reason might simply have been that I was happy and they couldn’t bear that they were not. They were still children themselves, after all–hard as dime-store crystals.

Stealing happiness, by any means necessary, is the subject of Half a Life. It is the memoir of a Bad Girl who refused to have a bad end. But it borrows nothing from the pastel racks of “personal triumph over adversity” tales. Instead, it whispers in a deceptively casual, even comic, vividly disturbing but seductive voice that, just maybe, the only chance for anyone born behind the eight ball of life is to cheat.

Ciment begins her story in 1964, when, at age 11, she and her family leave Montreal for a new life in Los Angeles. Her father, already emotionally awry, is dislodged by the trip, as if “some vital aspect of his being–his moral fiber, a stitch that fastens him to reality– got snagged on our front porch in Montreal so that as we roll across the country, inch by foot by yard, he slowly comes undone.”

Once in L.A. he takes a job with Sears, and the family settles deep in the Valley–a subdivision called Rancho del Sol, thirteen feet below sea level. There, the Ciments’ technicolor dreams of Southern California slide into dark surreality, a descent captured in Mrs. Ciment’s transit from mod adventuress, padding the sidewalks with her children and talking of possibility around every corner, to nail-bitten housewife, hemming her husband’s slacks with a staple gun and calculating the costs of divorce. As in her novel, The Law of Falling Bodies, Ciment regards L.A. with a loving disgust: loving because the world of childhood, even in shards, is forever the world of nostalgia; disgust because behind the city’s exhilarating newness and vulgarity there lies a desert, and an escapee’s memory of hurt. Early on in the book she writes:

“When the sun reached its zenith and the sidewalk turned scalding, my mother herded us home and sat us in front of the swamp cooler. It came with the house. I’d never seen anything like it before, and never have since. The cooler’s front looked like an old Chevy radiator filled to the brim with water; its back held a gigantic fan, with blades as long as baseball bats. When you turned it on, the floor and walls shook. Our sofa lay perpendicular to it and we sat in a row, our clothes flapping, our hair sticking straight out. I believe the cooler’s wind gave my mother the sensation of going places. It certainly gave my brothers and me the pomp and thrill of a hurricane ride. And for the rest of the afternoon until my father came home, we shouted over its blast or crooned songs–”You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” “Mama Said,” “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” (I chanted the “wimoweh” chorus). Normally, I never let myself sing out loud (I am tone-deaf and find melody as mysterious as night). But in the roar of the swamp cooler, I sang along with the family, crooning from the depths of my soul.

Then my father pulled into the driveway...”

Ciment’s father was deranged. He never touched his children, didn’t seem to know how. To him they were earthly persecutions, who ate his food, drained his paycheck, spilled his milk, wasted his electricity, expected warmth and, finding none, offered none in return. Existence, he seemed to imply, was indulgence enough for them; a gift or treat, so out of the question that their mother had to lie about the provenance of anything she bought her children. When he was crossed, he bellowed with rage; and when it rained and the freeways turned slick, the family dreamed relief might come with his car skidding off the road.

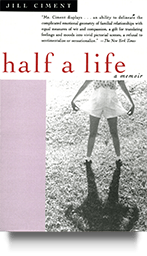

On the backjacket of Half a Life, Phillip Lopate praises the book, “especially the narrator and her father, two great characters.” Ciment writes with a novelist’s sense of pitch and roll, but the power of her book lies exactly in the recognition that these people are not characters. When the author-as-adolescent finds her mother choking with tears, pregnant with a fourth child, the family’s narrowest way out suddenly obliterated, her scheme to learn enough Spanish to find an abortionist in Mexico is plain-life despair. Of course, they never go to Mexico. Instead, the daughter lights out with two friends whose father works all night, sleeps all morning and drinks all afternoon, and vandalizes his boss’s house in an orgy of destruction that has you turning back to the photograph on the front cover, looking into the author’s haunting face and wondering, This girl? This girl ripped the flowery wallpaper off another girl ‘s bedroom wall? tore up her souvenir pillows? ruined a family’s furniture and scratched Fuck You into their stove? This girl had such hate for people she didn’t even know? A few months later the mother, “hot, huge, and immobilized,” stares at the TV in front of the swamp cooler, watching Watts burn: “Said if she wasn’t white and pregnant, she’d go down there and get herself a nineteen-inch color TV and an air conditioner.”

That the Ciments were a downwardly mobile, middle-class, secular Jewish family is important to note at this point. Nothing fit. Downward mobility barred them from the up-and-coming Jewish circles nearest them geographically; Jewishness (whether because of anti-Semitism or their own prejudices) separated them from the circles nearest them economically; secularism denied them the assurances of faith; and what they imagined as their “middle class” status even as the money ran out and the future closed in-offered no bolstering sense of class identity or tradition. When the father was finally evicted from the family, and the mother, unprepared for serious breadwinning and rejected at the welfare office, had to scrabble together an income, that last illusion also collapsed. What was left was America’s promise, “Only the strong survive,” with none of the distracting social drapery.

To a girl with ambitions, cheating must have seemed as natural as survival. Ciment doesn’t belabor this; she just tells her stories. How she determined that higher status was to be gained by being a bad girl at school rather than a good one. How she took a job forging opinion surveys, since fraudulent data meant quick results, hence more business and more cash. How she got a girlfriend to take her S.A.T.s for her when, having dropped out of high school and nearly drowned in New York’s demimonde, she realized a college art program was her only hope. How she abandoned herself to the tripper-than-thou world of Cal Arts, recognizing that “joining the exclusive ranks of the avant-garde is the quickest way in this world to up your class without money.” How she stole another woman’s husband, thirty years her senior, because she loved him and needed him.

That last theft is the most interesting, and not because of the age difference, or because of how it’s rendered in the book. (It turns out to be the one episode in the teenage protagonist’s life that is least carefully filtered through the adult author’s perception.) Like love, this little drama first appears a common thing, easily understood–boy meets girl, boy leaves wife, boy and girl live happily ever after. Yet, again like love, there’s nothing easy or common about it. Unlike Ciment’s other transgressions, this one–probably the most self-protective–cost somebody else plenty; and, unlike the others, it depended almost completely on chance.

Not long ago a friend of mine, talking about a woman jilted by her companion of twenty-some years, said, “After so long it’s not the man that matters, you know; it’s the life. It’s the life that you can’t bear to lose.” Ciment seduced her art teacher, Arnold, when she was about 17 and he had been married for twenty-some years. She knew nothing about the life my friend was talking about, but she knew she had to make, and save, her own. Ciment doesn’t disclose Arnold’s side of the story, but surely he faced a dilemma–whatever he chose to do would be a crime against love. For even if his marriage had been failing, still there was “the life,” there was history; and since he and Ciment have themselves been together for twenty-six years now, it’s probably safe to say he’s not one to take history lightly. So it all might have turned out differently, and Ciment, however adept at playing the angles in more material games, would have been powerless to change it.

Perhaps at the time, because of her youth, she didn’t think so much about what it meant that someone had to lose in this triangle, that someone almost always loses for the sake of someone else’s happiness, that it could have been her. But as a grown-up she writes with the solemn energy of one who knows how tenuous, how quicksilverish, how much of an uneven trade life can be.

Half a Life gets its grace from that knowledge. And in the end even Ciment’s father–”this unloved and unlovable man” whom she once tried to strangle–is spared from freakishness. Looking at his picture in a Time magazine article about “heart attack personalities,” she writes:

“I read about my dad, the quintessential type A personality, as you read another father’s long-lost diary–a man who must interrupt every conversation, a man who clenches his fist and pounds the table for emphasis, a man who explodes over trivia, a man who waits in stalled traffic like another man waits beside a ticking bomb. I studied the photograph. My father looked terrified laid out on the doctor’s white examining table like a corpse on a marble slab. I knew he saw his own death.”

He died finally, a passing that allowed his daughter to write this penetrating, soulful book.